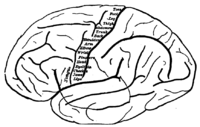

Many of the brain areas Brodmann defined have their own complex internal structures. In a number of cases, brain areas are organized into "topographic maps", where adjoining bits of the cortex correspond to adjoining parts of the body, or of some more abstract entity. A simple example of this type of correspondence is the primary motor cortex, a strip of tissue running along the anterior edge of the central sulcus, shown in the image to the right. Motor areas innervating each part of the body arise from a distinct zone, with neighboring body parts represented by neighboring zones. Electrical stimulation of the cortex at any point causes a muscle-contraction in the represented body part. This "somatotopic" representation is not evenly distributed, however. The head, for example, is represented by a region about three times as large as the zone for the entire back and trunk. The size of a zone correlates to the precision of motor control and sensory discrimination possible[citation needed]. The areas for the lips, fingers, and tongue are particularly large, considering the proportional size of their represented body parts.

In visual areas, the maps are retinotopic—that is, they reflect the topography of the retina, the layer of light-activated neurons lining the back of the eye. In this case too the representation is uneven: the fovea—the area at the center of the visual field—is greatly overrepresented compared to the periphery. The visual circuitry in the human cerebral cortex contains several dozen distinct retinotopic maps, each devoted to analyzing the visual input stream in a particular way[citation needed]. The primary visual cortex (Brodmann area 17), which is the main recipient of direct input from the visual part of the thalamus, contains many neurons that are most easily activated by edges with a particular orientation moving across a particular point in the visual field. Visual areas farther downstream extract features such as color, motion, and shape.

In auditory areas, the primary map is tonotopic. Sounds are parsed according to frequency (i.e., high pitch vs. low pitch) by subcortical auditory areas, and this parsing is reflected by the primary auditory zone of the cortex. As with the visual system, there are a number of tonotopic cortical maps, each devoted to analyzing sound in a particular way.

Within a topographic map there can sometimes be finer levels of spatial structure. In the primary visual cortex, for example, where the main organization is retinotopic and the main responses are to moving edges, cells that respond to different edge-orientations are spatially segregated from one another